In the wake of the FinCEN Files , lawmakers and regulators around the world have reacted to the unprecedented leaks. Beyond the $2 trillion headlines, the shock to some partly stems from the sheer scale of jurisdictions exposed by the publication with suspicious activity flagged in over 170 jurisdictions! According to the ICIJ, their investigation found that the banks “regularly processed transactions to companies registered in so-called secrecy jurisdictions and did so without knowing the ultimate owner of the account.” Notably, the ICIJ discovered that 20% of the reports featured a client utilizing an address in “one of the world’s top offshore financial havens, the British Virgin Islands,” which this week announced their plans to “unmask secret company owners,” a welcome move as the tiny island is home to 40% of the offshore companies in the world.

In the time since the ICIJ’s groundbreaking publication of the Panama Papers, the offshore world has definitely stepped into the spotlight. With more than a quarter of the world operating as some form of secrecy jurisdiction, the traditional stereotype of tax havens as small palm fringed islands is certainly shattered. How has our view of its risk evolved in the time since the Panama Papers were published?

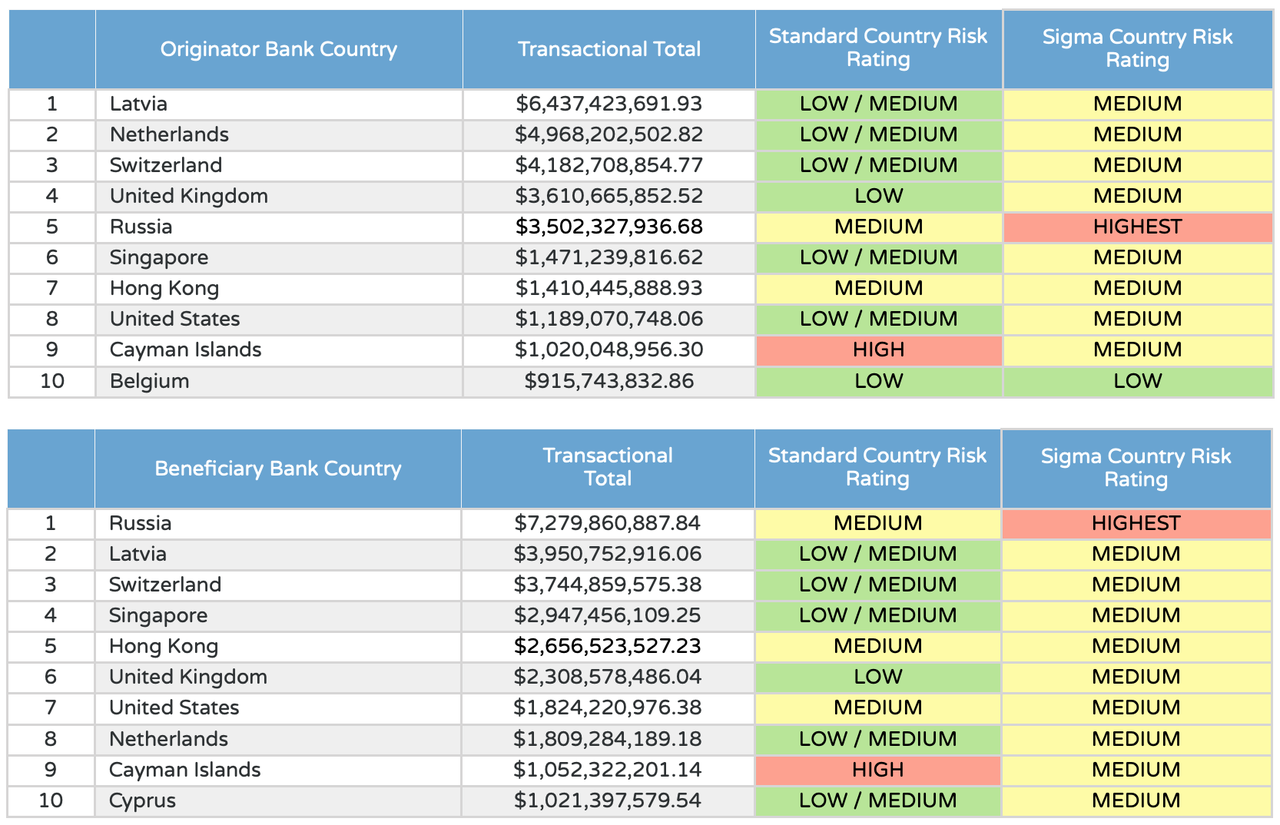

In light of the ICIJ’s acknowledgement of data integrity issues with SAR addresses in the FincCEN Files, a look at the top 10 originator and beneficiary bank countries might leave something to be desired for some, especially for those utilizing a standard, often static and non-granular, approach to country risk such as the one compared to Sigma’s ratings below.

Data captured from Sigma Terminal

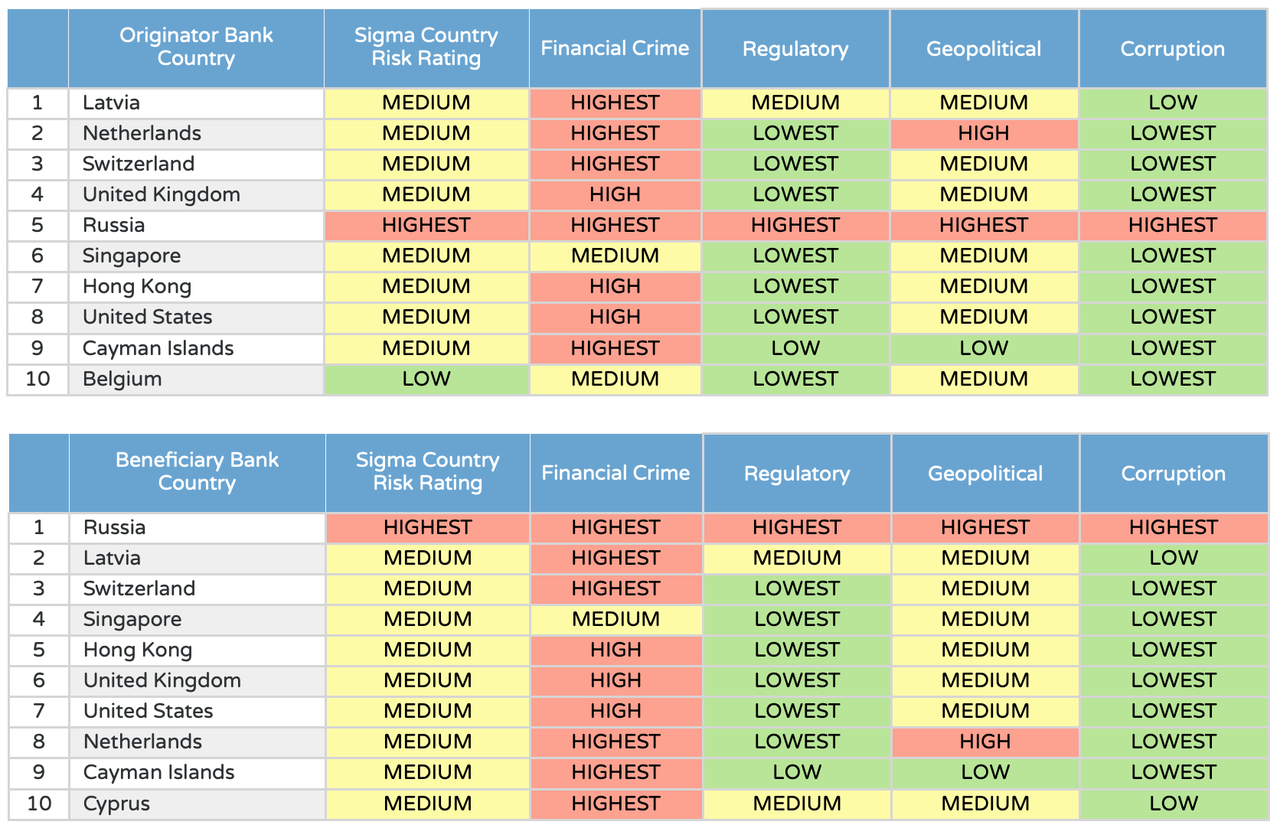

While some may express reservations at Latvia’s classification as ‘Low to Medium’ risk for financial crime, standard country risk ratings like the Basel AML Index lists Estonia, the epicenter of the Russian laundromat, as the lowest risk country in the world for financial crime. According to Basel, the low risk score is " largely driven by its good performance in the 2014 FATF Country Report”, which was the most recent assessment by the global watchdog and accounts for more than one third of its risk score. This is despite Estonia's proximity to Russia, a high-risk jurisdiction, which Basel acknowledged as a shortcoming of their methodology. While a lot has certainly changed in the last 6 years, substantial changes could occur in mere months as we highlighted with Malta in an earlier piece from two months ago, which saw the island nation go from one of the lowest risk countries in the world to the highest risk jurisdiction within the EU. The case of Estonia’s risk rating highlights the importance of a more contextual view of risk and the underlying drivers as demonstrated by Sigma’s Country Risk subcategory scores below.

Data captured from Sigma Terminal

While Russia is the only high-risk jurisdiction in the above analysis, a granular look at the ‘Financial Crime Risk’ sub-category illustrates the associated risks that may explain why these jurisdictions feature in the top 10 banking countries in the FinCEN Files. Furthermore, the additional sub-categories like ‘Regulatory Risk’ that comprise Sigma’s Country Risk Ratings do provide the contextual understanding of the risks. For example, while Switzerland and Latvia are both ‘highest’ risk for financial crime, the ‘Regulatory Risk’ associated with Switzerland does provide more assurances as to the risks associated with the jurisdiction. As the FinCEN Files have demonstrated, the scale and sophistication of financial crime highlights the imperativeness of a more holistic view of non-financial risk, and one that not only considers the entity itself and its associations as we’ve previously highlighted, but in this case, the overarching jurisdictional risk.

Sincerly,

Hamad Alhelal, CAMS, Director of Financial Crime Intelligence

To learn more about how Sigma’s Country Risk Ratings reach out at info@sigmaratings.com.

The leak and subsequent investigation of the FinCEN Files hit the financial services industry hard this past week - resulting in sharp declines in...

With the release of the FinCEN Files, what was a common denominator related to an international money laundering network, sanctioned in September...

When it comes to red flags for money laundering, knowing what warning signs to look out for is critical. Criminals have developed sophisticated ways...